FIELD STUDY ESSAY

Kewengi in Bameno—Martín Baihuaeri

Waorani brothers Martín and Manuel Baihuaeri envision a community-run ecolodge in the community-owned territory of the Baihuaeri, located in the heart of the Yasuní National Park, one of the most biodiverse areas in the world. The extended family could conserve their forests and weave their traditional economy into a global system with oil tentacles attempting to puncture the boundaries of the Intangible Zone, purportedly off-limits to extraction. Story captured by Haorong Lee.

The hum of the motor is drowned out by the sounds of the animals and insects that create a steady sense of reassurance on an otherwise foreign path. The forest is majestic and serene, a mixture of large trees scattered along the dense foliage encapsulating both sides of the river's edge, oftentime extending their branches towards the river as if offering us shade on our long journey. The air is humid, rain unpredictable, and the constant sounds of water brings back early childhood memories in Southeast Asia. Despite only having vision in one eye, Martin's senses are heightened and he and his brother Manuel point out the diverse wildlife that live close to the river – a stark contrast from the concrete oil boom towns that have scattered along the initial stretch of our journey from Coca. As dusk draws, the full moon illuminates the river's path, reflecting off the surface of the water. Manuel and Martin expertly maneuver around the sharp bends and turns of the river, we travel cautiously, avoiding fallen trees and debris that could damage the motor and leave us stranded. This is the arduous path that many Waorani frequent when they travel between Coca, a nearby city, and Bameno, within Amazonia. When we finally reach Bameno it is close to midnight, we see only where the moonlight touches but are aware of the complex landscape that is in store for us in the morning.[1]

Martin and Manuel are brothers from the Waorani Baihuaeri family. They live in Bameno, in the Ecuadorian Amazon. It is interesting to see how much the life of some Waorani families has changed while other parts stay the same. In the recent past the Baihuaeri family were multi-sited transhumant groups but now live semi-permanently, frequently moving between Bameno, Coca and other settlements within their territory. As we began to learn more about the Waorani lifestyle, it is evident how closely intertwined their lives are with nature. Daily routines involve visiting their manioc and agroecological groves to harvest produce, fishing from the river or hunting, as well as other forms of maintenance. Yet what has changed is their use of gasoline for transport and generators, gas stoves for cooking and electrical wiring systems in their homes.[2]

While traces of the traditional Waorani vernacular still remain, it is becoming increasingly urgent to explore how to adapt, modernize and revitalize their vernacular architecture to allow for better integration of modern-day technologies that the Waorani have welcomed into their lives. For example, the impromptu installation of electrical wiring systems in their naturally thatched vaulted architecture poses a serious fire and safety hazard for the Waorani. Traditional Waorani architecture is made up of materials sourced for the surrounding forest, the use of Mo and other leaves in their thatched roofs and open plan allow for passive air flow and permeability for the easy ventilation, not bound by the strict levels of water/fireproofing required by electrical systems. At the same time, it is important to preserve key elements of Waorani architecture and tradition rather than adopting or replacing structures with city-based architecture. The introduction of concrete schools with corrugated sheet metal roofs exist in contradiction to the natural and environmentally integrated methods of the Waorani. From the way the traditional foundation is created with pounded ground to the use of biodegradable materials and cyclical communal maintenance of the architecture, Waorani culture and tradition speaks of methods of living in harmony with the forest and its cycles rather than in separation.[3]

Despite the prevailing narrative of indigenous peoples being disconnected from the outside world, the Waorani community in Bameno are not a static culture and like many cultures continue to change over time. Internet connection is a scarce commodity here, in the limited lighted areas at night, people gather around the glowing screens of smartphones, contacting their family and relatives that have moved away into the city. Although many tragic stories exist in Waorani history, they continue to be resilient, curious and open to learn more about other cultures and lifestyles. International alliances have become critical to Waorani survival and plight for their lands. Their continued interest in maintaining contact echoes the desire to merge two different modes of living and knowledge sources without prioritizing urbanization and modern technology over their own. Waorani technology and knowledge can often be seen as more advanced than modern technology. In our treks through the forest, Martin was able to recognise a diverse range of plant and animal species, from smell and sound to even small traces on the ground invisible to the untrained eye. The Forest is a multidimensional source of life, where the Waorani obtain their building material, food, medicine, and many other essential resources. They have an integrated understanding of the life cycles of these materials and do not take more than they need. I wondered what could be done to incorporate off-the-grid modern services without surrendering the vernacular forest architecture in the now permanent settlements.[5]

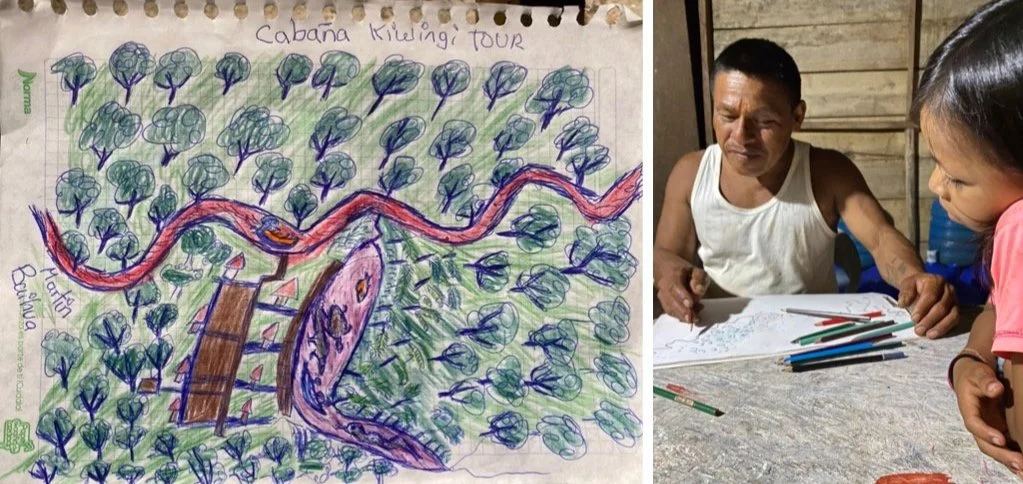

The Waorani people’s deep respect for nature can be most seen in their relationship with the nearby lagoon. The lagoon is a tranquil landscape of calm waters that is home to diverse wildlife and ecosystems. It was here that Martin and Manuel shared with us their desire to create Kewengi, a community-based ecotourism ecolodge next to the lagoon in the rainforest. Kewengi, the Waorani term for ‘love of life’, encapsulates the aspirations of the project as a sharing and healing ground for the Waorani.[6]

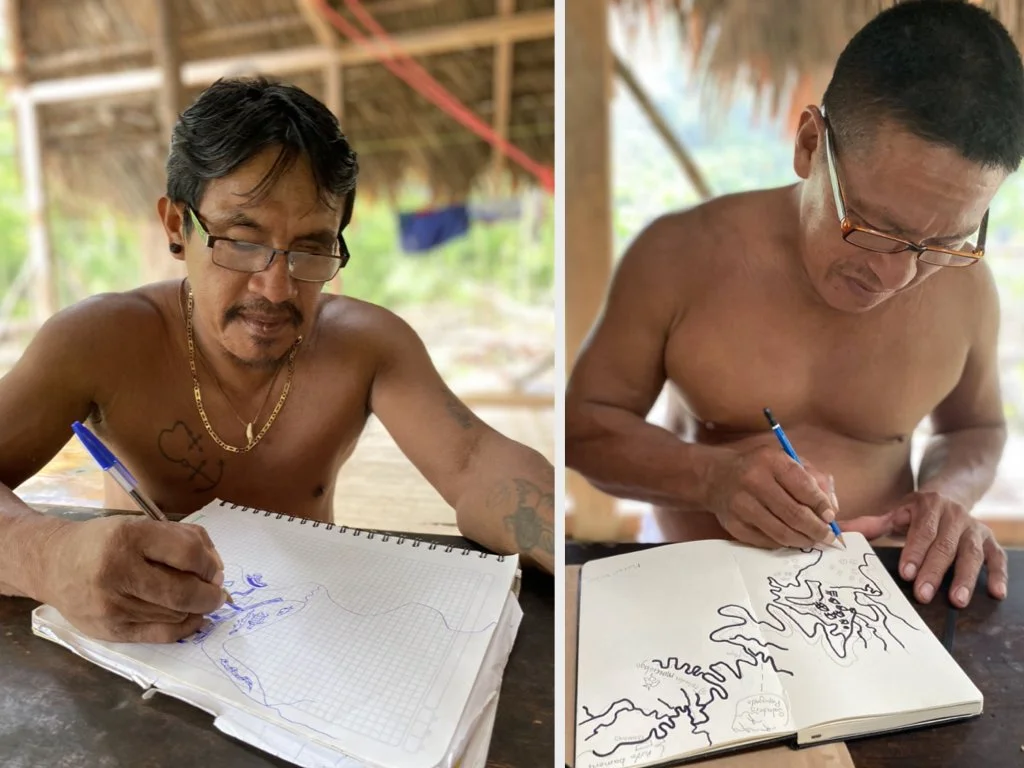

In recent years, the intermarrying between the Waorani and Kichwa tribes have consequently influenced the architecture and practices, as Carmen (Manuel’s wife) and Kichwa members of her community interweave their knowledge with Waorani knowledge. The first structure, already built by Manuel, Martín, and Kichwa partners, is an example of the melding of two cultures. As Martin and Manuel describe the project and begin drawing out plans[7] it is apparent the importance of the relationship to the forest and animals that coexist with the Waorani. In their drawings, animals and plants are fundamental, and depicted in the same size and level of importance as each other. In this communal space, nature takes center stage, not only in the physical sense but also spiritually through the ritual celebration of ancestors and forest spirits that exist in different timescales and spatial dimensions.[8]

In collaboration with Martin, Manuel, Carmen, our team from Yale Architecture and Ecuadorian-American architect Gabriel Moyer-Pèrez will work closely with the Waorani community and biologists. We hope to co-create a project that expresses the contemporary dreams of the Waorani as they weave themselves into a global society that has fully included their lands, but marginally included their wellbeing. Together we will weave the ancestral knowledge of the Waorani and Kichwa to create new forms of living with nature that can integrate their changing lifestyles while prioritizing their culture.[9]

Leveraging the expertise of these two indigenious tribes is crucial to creating a suitable and sustainable ecolodge. Therefore, we need to ensure that members of the community are actively involved in the design and development process. We will also draw inspiration from a Kichwa community in Mushullakta who have developed thriving land-based chakra (polyculture) systems that function not only as abundant natural resources for the community but also as natural gray and waste water filtration. The Mushullakta community have a deep understanding of how the different ecosystems of the forest interact and rely on each other, their complex chakra systems involve the careful selection of plants that aid the growth and resilience of each other. With this in mind, we hope to integrate a natural water filtration system through the chakras on the site to ensure sustainable use and waste mitigation while strengthening the existing ecosystems. Kewengi would be a composition of multiple interconnected sheltered spaces that would house visitors and members of the community. Dispersed throughout the site, the productive chakras and rainwater harvesting would provide for the daily needs of the community. Through a series of sheltered and open spaces the project will reimagine living with nature, providing spaces for community members and visitors to conduct workshops and share meals. Through these workshops and gatherings within and beyond the community, Kewengi will contribute to cultural revitalization among the younger generation of Waorani, bringing together multigenerational knowledge.[10]

The effects of Kewengi would be four-fold: a source of healing for the community, a knowledge-sharing platform for the Waorani and Kichwa, a collaborative experimental ground for modernizing traditional forms of architecture with new lifestyle requirements of the Waorani, and a new economic resource for the community that promotes their autonomy. With collective architecture that centers on the well-being of the community, community engagement and involvement are crucial to developing the project and ensuring its long-term sustainability. We hope to reflect the aspirations of the Waorani in this collaboration, not only through the planning but also in the craftsmanship, architecture and landscape. [11]

Like the Waorani word Waponi that can have multiple meanings all at once, Waorani culture is multifaceted and does not have to live in the dichotomy of being either primitive or modern. Moving forward we are hopeful for the positive change that Kewengi will bring to Bameno and its role in taking back control of Waorani life narratives from the external forces that have largely influenced their way of life, so that what has happened in areas like Coca does not continue to expand into Amazonia.[12]

Image Credits:

[1] Martin Baihuaeri on a boat to Bameno © Haorong Lee, 2022..

[2] Martin on the boat to Bambino © HL, 2022.

[3] Pinto’s Waorani style interior (left) and Martin’s Coca home (right) © HL, 2022.

[4] Audio of the Red Macaws © HL, 2022.

[5] View of the lagoon © HL, 2022.

[6] Drawing of the lagoon © HL, 2022.

[7] Video of Manuel drawing the natural environment © Ana Maria Duran Calisto, 2022.

[8] Carmen and her grandson in the cabana (left) and elevation of the lagoon (right) © HL, 2022.

[9] Martin’s drawing the lagoon and Manuel drawing with Tatiana by his side. © HL, 2022.

[10] Forest view © AMDC, 2022.

[11] View from Lagoon Cabana © HL, 2022.

[12] Kewengi structure © AMDC, 2022

Martín Baihuaeri is a proud member of the Baihuaeri family, a Waorani indigenous group from the Ecuadorian Amazon. Along with his brother, Manuel, and sister in law, Carmen, Martín hopes Kewingi can be a catalyst for change and healing, a means for the Waorani to take back control of their life narratives and weave together their knowledge.

Haorong Lee is a graduate architecture student at Yale University, she is interested in the nuances of placemaking and the art of craftsmanship within the tropics, through the relationships between vernacular architecture and nature.

Guest Editor: Ana María Durán Calisto