REVIEWS

Book Review

— Charles C. Moorhouse

Rem Koolhaas and Prospective Preservation

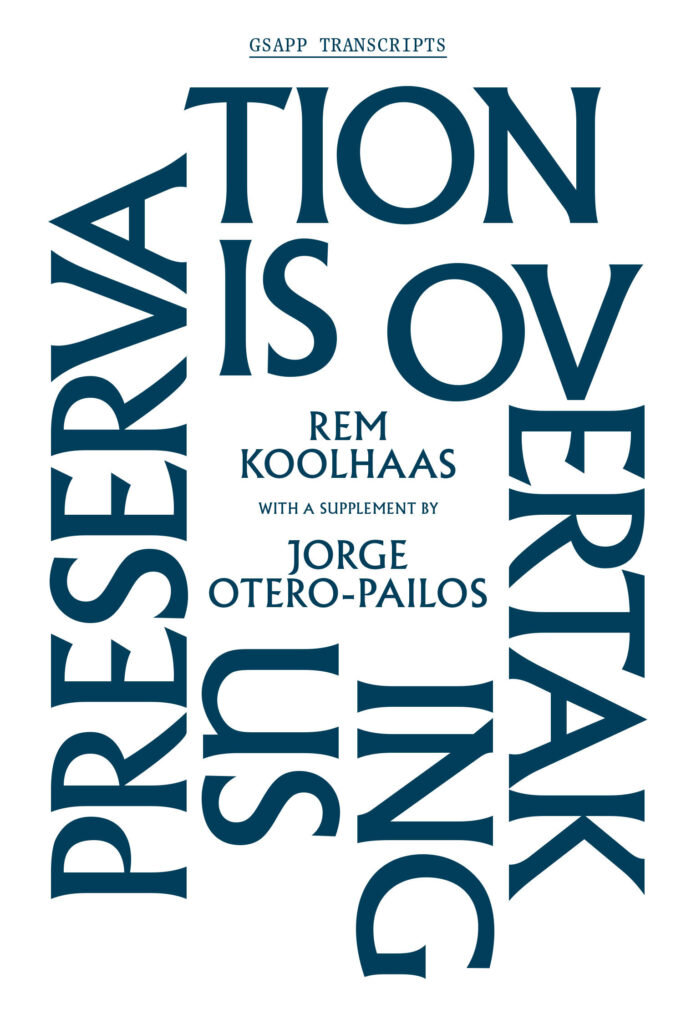

Preservation is Overtaking Us is a transcription of two lectures that Rem Koolhaas presented at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture in 2004 and 2009. The lectures are supplemented by Architect and Preservationist Jorge Otero-Pailos, who pieces together OMA’s unwritten preservation manifesto based on the lectures as well as a review of the Venice Biennale exhibition by Koolhaas and his firm OMA in 2010 entitled Cronocaos.

Cover image: courtesy of Columbia Books on Architecture and the City Press, Columbia University

To say that preservation is overtaking us is a bold statement; a warning of an epidemic that needs to be addressed. The urgency may be lost on places like Calgary where the “new” frequently replaces the “old”. This could be in part due to the fact that in North America our built heritage does not date as far back as those in Europe, or perhaps due to development pressures brought on by cycles of economic boom. 2017 marks the 150th anniversary of Canada so perhaps it is time to reevaluate the worth of our built heritage. Architect Rem Koolhaas offers us a modern examination of global preservation practices in his lectures and exhibition. For Koolhaas, the future of architecture is preservation. The striking concept from these works is that modern society is so obsessed with the past that time is no longer functioning as a linear or chronological paradigm. It is chaotic to the point that heritage is becoming our future[1] (hence the title of the exhibition Cronocaos derived from the words “chrono” and “chaos”). Through exploring past projects and researching global trends, Koolhaas is providing a much-needed revisiting of preservationist thinking.

The current, and generally accepted, preservationist discourse can be attributed to two conflicting paradigms put forward by Viollet le Duc (d. 1879) who supported preservation as the restoration of the idealized form and John Ruskin (d. 1900) who supported the preservation of authenticity of craftsmanship and ageing. Both streams of preservationist theories still dominate the conversation to this day. Both Le Duc and Ruskin were working in the ‘modern’ era that witnessed the invention of photography and refrigeration, among others.[2] Preservation began with saving ancient monuments and religious buildings.[3] Today preservation can include any tangible or intangible heritage. The age of which a historical designation is given is creeping closer and closer to the present as illustrated by a private residence completed by OMA that was designated upon completion.[4] Koolhaas believes it is not long until preservation is no longer a retroactive process, but a prospective one.[5] Koolhaas explores this idea of prospective preservation with his “Barcode” scheme for Beijing. This hypothetical urban plan superimposes striped zones of preservation across the city. Buildings in these strips would be preserved regardless of their cultural and sociological relevance, maintaining an authentic historical timeline. Buildings between these preserved strips would be reserved for new construction. These zones would constantly be in flux and subjected to demolition and rebuilding as their relevance faded. This allows for a constant stream of creativity and innovation within an eternally planned tabula rasa contrasted next to an authentic slice of history frozen in time. As an urban planning tool, zones could be designated to specific decades or eras. While this scheme addresses preservation’s desire to maintain authenticity both in structure and context through a democratic and dispassionate way,[6] it ignores the random and uncontrollable nature of architecture as cultural development. Who is to say what building or place will take on cultural significance? While the “Barcode” scheme is flawed, it is Koolhaas’ attempt to answer the age-old question of what is worth saving and what do we erase that is of importance.

Both Preservation is Overtaking Us and Cronocaos explore more than just the “Barcode” scheme, it examines many of OMA’s past projects. In an almost revisionist manner, Koolhaas re-frames OMA’s body of work to showcase preservation as the central focus since the office’s beginnings,[7] claiming that he merely did not realize he was doing so at the time.[8] This is a seemingly convenient albeit not implausible narrative as he appears to be seeking shelter from his own view of an increasingly mediocre profession of architecture that is driven by the market economy. Starchitecture and design driven by capitalism has resulted in an environment of excess or “bling” which is expressed through superficial forms.[9] For Koolhaas, preservation presents a formless architecture,[10] one where the form is already to a certain extent determined, and it is the architect’s responsibility to creatively marry a program that is foreign to the host form. This practice of preservation is more aligned with the concept of adaptive reuse as it allows for the creative insertion of new life into the existing built environment. This is neither Le Duc’s theory of restoration nor Ruskin’s theory of authenticity, although it often falls on the spectrum between these two contradictions.

Koolhaas attempts to highlight various contradictions that continue to plague preservationist practice, not always providing a solution, but to simply raise the issue for discussion. On the one hand Koolhaas claims that so much of the world is becoming preserved (12% at the time of the exhibition)[11], that soon architects won’t be left with any blank slates for new creations and large scale master plans (the likes of which were seen in the 60’s and 70’s, a time that Koolhaas views as the last great period for architects when the West completed urbanizing[12]). In contrast, he also argues that preservation is not inclusive enough as he defends the value of modernist works, including brutalism, which too often is unappreciated for its aesthetic in the present. We do not know what will be appreciated in the future, so how can we then erase in the present? Preservation cannot be a subjective process which harkens back to his “Barcode” scheme in which he democratically and objectively attempts to preserve Beijing. This subjectivity in preservation can be seen in Calgary’s treatment of its own brutalist heritage. While work is being done to protect brutalist works, such as the Centennial Planetarium and Century Gardens, others like The Calgary Board of Education building risk demolition due to its perceived aesthetic with the general public.[13] The problem with a subjective view of what to save is that what is deemed unpleasant and irrelevant today, may become valued and respected by future generations. The present is so encompassing that it is difficult to remove ourselves to see the bigger picture.

Koolhaas’ theories on preservation and time can at times be unclear. Preservation is Overtaking Us and Cronocaos need to be understood together as the two alone seem fragmented. The verbal expression of ideas in the lectures fills the gaps of visual graphics and walls text found in the exhibition. Together they illustrate Koolhaas’ main thesis which is that preservation (and time) is no longer linear and that to address the past we must plan for it in the present and for the future. This notion of prospective preservation is meant for a global audience, and yet sometimes we may not feel that heritage is being preserved fast enough in North America. Perhaps the solution is as Koolhaas suggests; that preservation should not be a reactive measure, but a proactive one.

References:

[1] Rem Koolhaas. "Cronocaos." Lecture, Festival of Ideas for the New City, New York, New York, May 4, 2011. Accessed March 25, 2017. http://oma.eu/projects/venice-biennale-2010-cronocaos.

[2] Koolhaas, Jorge Otero-Pailos and Jordan Carver. Preservation is overtaking us. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and The City, 2016: 14.

[3] Ibid: 15.

[4] Ibid: 16.

[5] Ibid: 16.

[6] Ibid: 17.

[7] Ibid: 83.

[8] Cronocaos. New York: New Museum, 2011. Wall text.

[9] Rem Koolhaas, Jorge Otero-Pailos and Jordan Carver. Preservation is overtaking us. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and The City, 2016: 24.

[10] Ibid: 93.

[11] Cronocaos. New York: New Museum, 2011. Wall text.

[12] Koolhaas, Jorge Otero-Pailos and Jordan Carver. Preservation is overtaking us. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and The City, 2016: 11.

[13] Trevor Howell. "Architects rally to save ex-CBE HQ." Calgary Herald, November 12, 2013. Accessed March 25, 2017. http://www.pressreader.com/canada/calgary-herald/20131112/281754152088633.

Look for this title at The FOLD's local Recommend Shelf at Shelf Life Books in Calgary.

Charles Christopher Moorhouse is an Intern Architect working in Calgary, Alberta. He is interested in heritage architecture and how time manifests itself in the built environment.