REVIEWS

pond-centric Urbanism

— Mashuk Ul Alam

Fresh water ponds as not only an urban natural resource, but as a remnant cultural artifact of Rajshahi

The relics of an ancient ghat landing in the water. It is said that the stairs of many ponds like this was designed so that pregnant women could easily access the water. Image © Ul Alam, Mashuk, 2019.

There is a pond at the entrance of Rajshahi City. It was created from a tributary of the Padma (the stream of the Ganges in Bangladesh) and is known as “Sharmangala” (স্বরমঙ্গলা)[1]. The drift of the tributary has died gradually after the embankment of the Padma and its course were encased in the mid-19th century in a box-culvert that marked a simulacrum of hydrological infrastructure in the developing city. Today, the pond waits to be devoured: encroached by residential buildings on one side and a national highway on the other, suffocating under the veil of urbanization just like the historical environment of the city.

Further inside the older parts of the city, every neighbourhood has at least one heritage pond. Some neighbourhoods are named after their heritage pond or are familiar because of the local legend or history of the pond’s genesis. Sonadighir Mor or the node of Sonadighi, for example, was named after the pond “Sonadighi” which literally translates as “the Golden Pond.” This name became popular because of the golden pot used to distribute the water of the reservoir to the people of the city; the metal of the pot was supposed to keep the water from contamination. These are just a few of the neighbourhoods named after ponds. Others include Sagorpara, a major residential neighbourhood in the city, which was named after its pond “Sagordghi,” which means “the Great Pond,” because of its enormous size and grandeur. Similarly, “Baliyapukur” (“Sandy Pond”), “Daspukur” (“Ponds of Slaves”), and “Meherchondi Dighi” (named after the legend of two struggling lovers of mixed religion, Meher and Chondi).

In the mid-18th century, a large number of displaced people from adjacent Murshidabad (currently a district of West Bengal, India) migrated to Rajshahi. They dug numerous ponds for holding fresh water and built courtyard houses on the elevated land. The distinctive circulation of golis (alleys) in the city, and the streets running through them, expose the ponds opening at the ghats (water terraces); sometimes the alleys and streets encircle the pond. The thermal comfort created by the microclimate around the ponds offers respite and repose to the inhabitants of this semi-arid region and creates a sense of place where they can gather and practice different water-centric social activities, forming a cultural pattern.

Neighbourhoods are named after the names of ponds. The Jubilee Pond was more famously named Sonadighi, which literally means “the Golden Pond.” The fresh and pure water of the reservoir was distributed among the residents in times of water scarcity. Water collection and distribution was done with golden pots—to avoid a metal reaction and water contamination. The neighbourhood was named after the pond, Sonadighir Mor. Image © Ul Alam, Mashuk, 2019.

Unfortunately today, the pond water is no longer potable due to pollution caused by overuse and stagnation. Rising privacy concerns among people who can easily access groundwater inside their houses discourages swimming as well, limiting the pond’s use to being simply a place for washing clothes, or cleaning. Women tend to find comparatively cloistered ghats that are hidden from outsider’s eyes to chat sitting on the concrete-paved banks. Children run around the narrow strip covered with grass or jump into the water from the branches of a nearby tree. They also enjoy playing “frog-jump,” a game of making waves in the water by throwing pebbles. Men are sometimes seen catching fish, bathing cattle, or cleaning electric auto-rickshaws. Most of the paths circulating around the ponds are made with concrete, sometimes with an elevated retaining wall. In some remaining parts, the cohesion between land and water creates the most favourable condition for ecological growth, hotspots for local biodiversity. In the winter, the ponds shelter and feed thousands of water birds migrating from cold regions. During the dry season, some ponds dry up completely creating pockets of urban playgrounds. In the monsoon season, they rejuvenate. Flooding the surroundings, they create an infinite coexistence of land and water that is hemmed by a lush greenery, a customary view of the Bengali landscape.

View of residential development surrounding the ponds, with a street at the circumference creating a pond-centric neighbourhood. Image © Ul Alam, Mashuk, 2019.

Ponds and their surroundings are not only the only source of urban green space in the city, they also comprise nearly 30% of its open spaces.[2] Many rich and influential dignitaries who came to Rajshahi, the newly made divisional capital under British Colonial Rule in the first part of the 19th century, constructed ponds individually or collectively as utilitarian spaces for manifesting personal or social power. These ponds are enormous in size, usually with multiple staired ghats and one or more religious structures, mostly temples or matha. The majority of the relics of these historical installations are hidden from the eye. Clusters of courtyard houses line a pond and the area beyond them is layered with meandering streets, ghats, religious structures, and scattered vegetation that constitute a “Para” (পাড়া) or neighbourhood, which is the fundamental unit of the entire spatial pattern of the old town.

In 1961, there were 4,238 ponds, canals, and wetlands in the city. In 1981, the number was 2,271. In 2000, the number stood at 729. Today, the city has only 214 waterbodies. Over the last five decades, the city has lost approximately 4,000 ponds due to indiscriminate earth dumping and unplanned urbanization [3]. To stop these atrocities, the High Court on December 13, 2010, issued a directive to stop the filling in of all kinds of wetland in and around the city following a writ petition.[3] Motivated by its other environmental initiatives[4]—which have earned it a global reputation as a clean city for its rapid reduction of harmful particles in its air and allowed it to receive the "Environment Friendly City of the Year 2020" award—Rajshahi City Corporation (RCC) has adopted a development project entitled Natural Water Bodies Conservation and Development in Rajshahi City to protect the ponds.[5] In addition to this, Rajshahi Development Authority (RDA) has added a “list of conservation of ponds” to their 20 years’ Development Plan, RMDP 2004-2024.[6] However, the initiations are dubious, due the possibility of its outcome to be confined to beautification only.

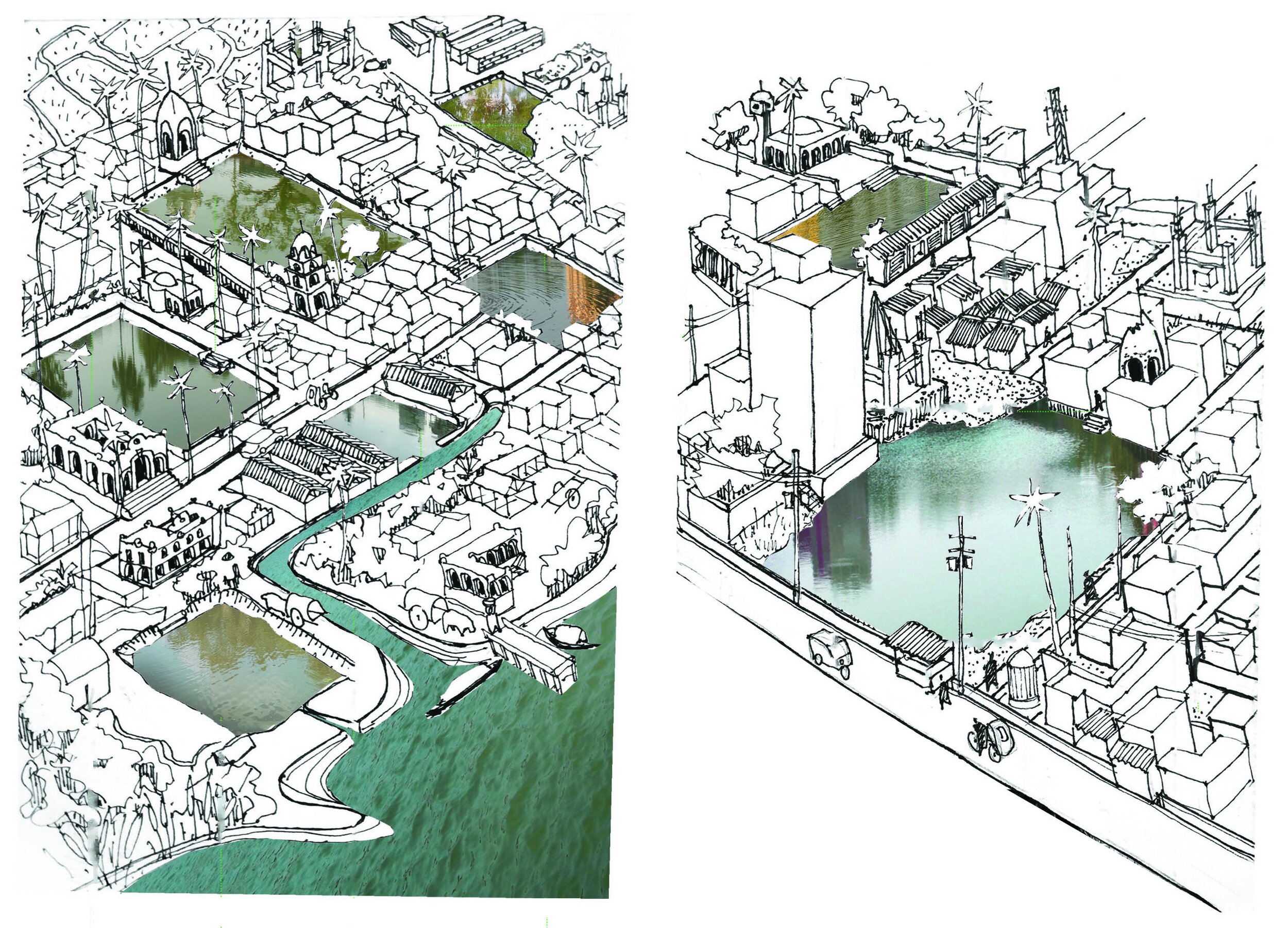

Conceptual drawings featuring the relationship between ponds and the urban form, revealing the weight of the pond as the most important natural system of the city. Drawings © Ul Alam, Mashuk, 2020.

Ponds are the only remanent urban socio-cultural artifacts of the city. The residual traces of history and the associated intricate sense of community developed over time remain to be rediscovered and redesigned in order for them to intertwine with modern urban infrastructure and changing social norms and culture. If conscious rediscovery and redesign is not embarked upon, these biological birthmarks will be erased from the urban fabric and the people of Rajshahi will soon be living among the tombstones of the city, with their famous ponds writing the epitaph of the city’shistoric and intrinsic urbanism.

References

[1] M. Siddiqui, “রাজশাহী মহানগরীর হারিয়ে যাওয়া পুকুর ও দীঘি”, Rajshahi City: Past and Present, vol. 2, no. 26, pp. 170-226, 2012.

[2] S. Doza, "Analysis and Identification of the Spatial Pattern in Rajshahi Old Town", M. S. thesis, Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology, Dhaka, 2008.

[3] “Pond filling plagues Rajshahi city,” Dhaka Tribune, Sep. 01, 2014. [Online]. Available at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/uncategorized/2014/09/01/pond-filling-plagues-rajshahi-city-2. [Accessed: Sep. 23, 2019].

[4] E. Graham-Harrison and V. Doshi, “Rajshahi: the city that took on air pollution – and won,” The Guardian, Jun. 17, 2016. [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/17/rajshahi-bangladesh-city-air-pollution-won. [Accessed: Sep. 23, 2019]

[5] T. D. Sun, “RCC to conserve 22 ponds in Rajshahi city,” Daily Sun, 08-Oct-2018. [Online]. Available at: https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/341508/2018/10/08/RCC-to-conserve-22-ponds-in-Rajshahi-city. [Accessed: Sep. 23, 2019].

[6] Rdaraj.org.bd. 2021. List of Conservation of Ponds | Rajshahi Development Authority. [online] Available at: https://rdaraj.org.bd/list-of-conservation-of-ponds/. [Accessed 1 August 2018].

Md Mashuk Ul Alam is an architect native to Rajshahi, a metropolitan city in Bangladesh, whose research explores how pond-centric urbanism can not only solve environmental problems like extreme and semi-arid climate or excruciating pluvial floods, but can also sustain the cultural image of the city and support interpersonal memories of its residents. He participated in the 2021 WriteON workshop series, Amend.